Changing global and political landscapes have made the kind of broad and bipartisan agreements reached in the 1970s seem impossible.

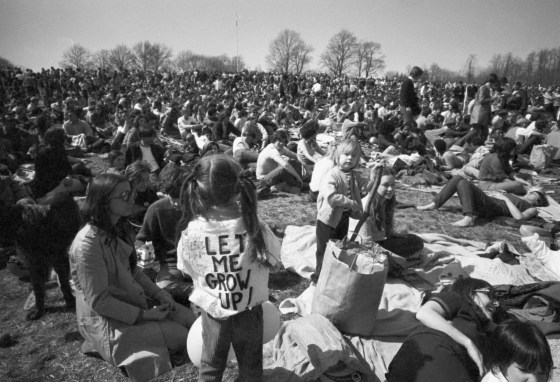

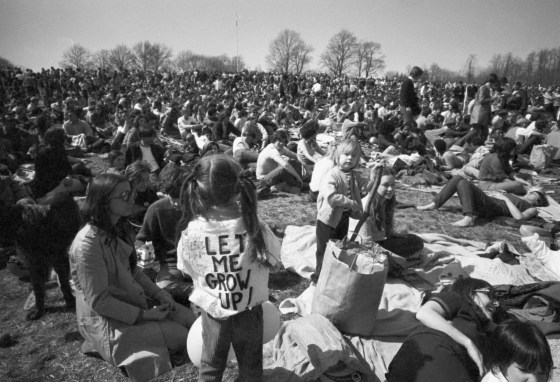

A young girl wears a "Let Me Grow Up" sign as residents mark Earth Day in Philadelphia's Fairmount Park on April 22, 1970. AP

April 22, 2020, 3:15 PM UTC / Updated April 22, 2020, 5:19 PM UTCThe first Earth Day, held on April 22, 1970, marked a turning point for U.S. environmentalism, capturing the growing activism of the 1960s and putting the country on track to create the Environmental Protection Agency and many major pieces of legislation in the 1970s.

Fifty years later, those efforts are at risk of being rendered null.

For the 50th anniversary of the first Earth Day, veteran climate activists are offering words of warning about the changing global and political landscapes that have made the kind of broad and bipartisan agreements reached in the 1970s seem impossible.

“What’s disturbing to me about what’s happened over the last 50 years is this steady drift of the Republican Party toward opposing environmental action and dismantling 50 years of environmental progress,” said Michael Mann, a professor of atmospheric science at Pennsylvania State University.

And with countries around the world in the grips of the coronavirus pandemic, some experts fear that climate action could fall by the wayside as nations attempt to restart their economies. Rather than investing in infrastructure to support renewable energy and focusing efforts on reducing carbon dioxide emissions, for example, countries could revert back to the status quo in a bid to recoup coronavirus-related economic losses.

But the path ahead won’t be easy. Humanity is quickly running out of time to keep global warming below2 degrees Celsius (3.6 Fahrenheit) and slow the most damaging impacts of climate change. And even with aggressive action, the planet is still at risk of rising seas, drought, wildfires, extreme weather and other potentially damaging consequences of the warming that has already happened.

Still, David Muth remembers when taking environmental action wasn’t always a partisan fight.

As the director of Gulf restoration for the National Wildlife Federation, Muth knows that climate policies have always been hard-won, but beginning in the 1960s, as the severity of human-caused pollution was becoming more apparent, people started to demand change.

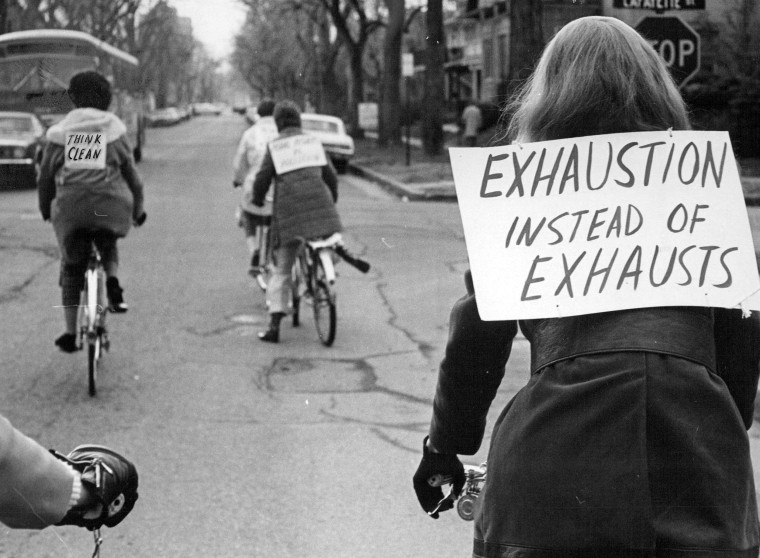

It was a movement that sparked huge protests, teach-ins and culminated in the organization of the first Earth Day, an event devoted to raising public awareness about threats to the environment.

The mobilized efforts paid off. Over the next decade, a flurry of science-based legislation aimed at protecting the planet was introduced — a legislative heyday for environmentalists that included the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970, passage of the Clean Air Act in 1970, the Clean Water Act in 1972 and the Endangered Species Act in 1973, among others.

“We cleaned up the surface waters of the United States, we cleaned up the air, we salvaged many species on the brink of extinction, we took a hard look at how we treat wetlands and barrier islands, and we didn’t do a lot of stupid things because of the National Environmental Policy Act,” Muth said. “All these seminal pieces of legislation were passed in the 1970s.”

This period of time was significant because it kicked off an era of mostly bipartisan support for environmental action, said Mann, who rose to prominence after publishing a paper in 1998 that showed temperature changes on Earth over the past millennium. The plot, which was almost flat before curving sharply upward in the 20th century from human activities, was dubbed the “hockey stick” and has become an iconic representation of humanity’s role in global warming.

Though support for climate science now tends to be divided along party lines, many key environmental policies were introduced by Republican administrations, including those of Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush.

While not perfect, some of the most pivotal environmental policies from the 1970s have had a demonstrable impact. In an editorial published April 17 in the journal Science, James Morton Turner, an associate professor of environmental studies at Wellesley College, and Andrew Isenberg, a professor of American history at the University of Kansas, examined their legacy.

“In 2010, the Clean Air Act and its 1990 amendments were estimated to prevent 3.2 million lost school days, 13 million lost workdays, and 160,000 premature deaths,” they wrote. “The Clean Water Act is responsible for substantial declines in most major water pollutants. Scientists estimate that the Endangered Species Act has prevented the extinction of 291 species and helped 39 species to a full recovery.”

But President Donald Trump has moved to significantly weaken many existing environmental protections.

In August 2019, the Trump administration announced changes to how the Endangered Species Act would be applied, reducing protections for some species while also making it easier to remove a species’ endangered classification. The following month, the administration rolled back clean water regulations implemented by the Obama administration that limited chemicals and harmful substances that could flow into streams and other waterways. And in November 2019, Trump began the year-long process of withdrawing from the landmark Paris climate agreement.

According to The New York Times, these changes are among more than 90 environmental rules that have been reversed or weakened since Trump took office.

“It’s very frustrating, this whole attack on our system of environmental protection,” Muth said. “We’re rolling the dice unnecessarily.”

But the post-pandemic recovery period could also give countries a chance to reassess.

“As we move out of the emergency response phase, do we put investments into the economy of the future, or do we put everything back to where it was?” said Robert Kopp, a climate scientist at Rutgers University.

But the pandemic could also induce the opposite response, by forcing people to take stock of their values and broader societal goals. For instance, the outbreak demonstrated how lifestyle changes can have an impact — however fleeting — on the environment. Countries under coronavirus lockdowns, such as China, Italy and the U.S., experienced unintended climate benefits such as declines in pollution and greenhouse gases as a result of reduced air travel, restrictions on movement within cities and significant slowdowns of industrial activities.

While these climate benefits are only temporary, they did demonstrate what can happen even on short-term scales, according to Mann.

“We can see in real time the impact that we can have on the environment if we choose to curtail certain type of activities,” he said.

The pandemic has also demonstrated the importance of cooperation among countries on matters of global importance. After all, climate change — like a virus — pays no regard to borders.

Mann maintains that though the post-coronavirus recovery will likely be challenging, the pandemic’s silver lining could be that it sets off efforts to protect the health and safety of people, their communities and the planet — similar to the citizen-led initiatives that surrounded the first Earth Day celebrations.

“We have a real opportunity here for change,” he said. “As they say, it’s always darkest before dawn. We may see the tipping point we’ve all been waiting for on climate change action.”

Denise Chow is a science and space reporter for NBC News.